This will be my final blog post as part of my internship with the ‘Electrifying the Country House’ (ECH) project. It has been quite a journey! I enjoyed many parts of the process: learning about the development of electricity in late nineteenth century England, discovering the aristocrats that helped move the development along, and uncovering the fascinating personalities of the engineers who helped electrify the country houses. The final part of my internship was more hands-on – it gave me the opportunity to be directly involved with the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) grant application. I was responsible for drafting several sections in the application, one of them being the ‘Academic Beneficiaries’: listing which groups of scholars would benefit from this project.

Michael, the postdoctoral researcher of the ECH project, delegated this task to me in part because I was a literary studies student. I was able to identify areas that might not initially be obvious to someone working within the history of science. This was the case in previous assignments; for example, I had come across the aristocratic and elite social group, ‘The Souls’, which gathered in the home of Lady Desborough. Among her guests at these gatherings were Sir Winston Churchill and science fiction novelist H. G. Wells. Because of her involvement with notable aristocratic figures who were involved with the domestication of electricity, I suggested that the project pursue Lady Desborough’s letters in the Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies. I was pleased to discover that ‘The Souls’ had yet to be considered by the ECH project, and that these archives could be an interesting line of inquiry.

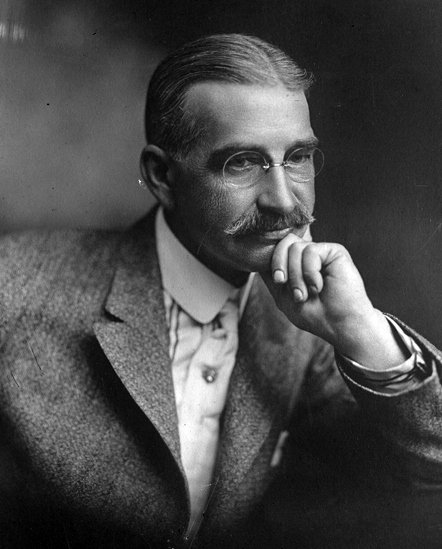

Turning my attention to the ‘Academic Beneficiaries’ of the ECH project, I immediately saw that this project would have far-reaching impacts on the study of English literature. Two of the primary texts are literary ones: The Master Key: An Electrical Fairy Tale, Founded Upon the Mysteries of Electricity and the Optimism of Its Devotee (1901) was written by L. Frank Baum, best known as the author of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, and Hodge and His Masters (1880) penned by Richard Jefferies, a nature and children’s writer. Both authors are known as early writers of science fiction. Literary scholars of the late Victorian era and early 20th century writings, specifically, work with texts produced during the age of electrical technology developments; such an exciting technological progress would have greatly inspired authors of the time. Findings from the ECH project will thus be helpful in providing a historical context for the analysis of these literary texts, as well as other works of early science fiction.

Other academic beneficiaries would be those working in tourism studies, a subject which usually incorporates a practical element into its student programmes. This project’s partnership with country houses such as Harewood House and Hatfield House can therefore serve as a helpful model of academic institutions collaborating with sites of tourism. The ECH project will also be assisting with the development of new media for these country houses, incorporating information gathered on the history of electricity to provide visitors with a more nuanced perspective of the houses as historical sites. Tourism students and academic staff will be able to observe the impact and usefulness of these media on touristic sites, and apply it to their own projects.

At the moment, the drafts of the AHRC application are being reviewed and edited, and I find myself coming to the end of my internship. Looking back on the past few months, I’m grateful for the opportunity to work with the ECH project as I was able to develop many transferable skills. One of the most important skills developed was analytical research of archival materials. Being able to pinpoint the location of historical sources will prove important in any future work I do – academic or otherwise. I have also gained more confidence in my ability to conduct research on any given topic, independently or collaboratively. As I was also working on my thesis and running my own research group alongside this internship, this project helped me develop the added skill of organisation. It allowed me to hone my ability to prioritize, and also to be more communicative in order to ensure that all activities run smoothly.

As co-founder and co-organizer of activities for my own research group, Reading the Fantastic, my internship was helpful in understanding the funding application process for a large-scale project. In particular, I was able to obtain a more concrete grasp of the term ‘impact’ in terms of research activity. This will help in the planning of future research activities, and it will especially help in applying for future research funding.

Finally, I was given a glimpse into the long process of putting together a large-scale project and I am now able to appreciate the subtleties of how a project comes into being – from being inspired by previous projects, to strengthening existing partnerships, and then searching for new ways to constantly improve the project.

In short, this internship provided me with the invaluable opportunity to not only grow in terms of knowledge, but also in terms of managing and expanding a project. I would like to give my heartfelt thanks to Michael, who took a chance on a literary student such as myself, and for being such a wonderful mentor throughout this journey. I hope that the ‘Electrifying the Country House’ project continues to grow, and I’m sure I’ll be seeing more of it in the future.