As the project comes to an end, we are now ready to unveil the new history of electricity house trails we have produced for Standen and for Lotherton Hall. These are available to view and to save on our Downloads page, along with a couple of other documents detailing our resources . These trails have been designed to fit with existing trails used in each house, using templates supplied by the houses. We are in the process of producing a one-off print run for the houses, which we will send to them, and after that each house will be able to print more as needed.

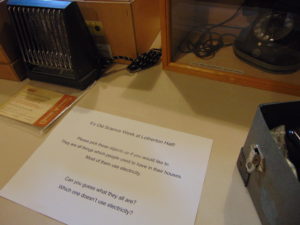

Each trail gives visitors an idea of the kinds of electrical artefacts and systems present in the house – such as the electrified candlestick at Lotherton Hall, pictured left, and the pressels at Standen, below. When developing these, it was important for us to get input from house volunteers and guides, as they know best the kinds of things visitors want to know, and the questions they ask, and will be the first point of contact if visitors want to know more about content of the trails. To get this feedback I visited each house to present early drafts of the trails, and discussed the content with guides and volunteers. Although with limited space it was not possible to incorporate all suggestions into the finished drafts, it was very useful to run these early versions past the people who interact with visitors on a day-to-day basis.

One useful discussion we had was how much technical detail ought to be included. There are visitors who appreciate this information – I have met several current or former electrical engineers at various houses over the course of this project myself. However, we agreed that on the whole visitors do not come for, or expect, electrical history, and so the interpretative content should focus on the social history, with a few details about the technical aspects of the system for those who want this information. The trails therefore contain a lot of social history content from Professor Gooday’s and Dr. Harrison-Moore’s work as it applies to each of the houses, for example emphasising the significance of class and gender in people’s responses to electrical technologies. Each makes reference to nineteenth-century fears about electrical accidents, the design of electrical fittings, and the use of electricity for communication within the house.

In addition to these full trails we have also produced a template schools’ resource for Lotherton Hall – a shorter trail with activities – and are also producing a children’s trail for Standen. The challenge for these resources was to distil some key points out of the research and to convey them in a way which would appeal to a young person moving around the house. As with most of the work we have produced as part of this project, the key was to focus on the human stories and relatable imagery, such as ladies worried that the bright electric light would be bad for their skin, or unreliable lights going out in the middle of a meal, and where possible to include children or young people – such as the Beale children playing billiards by electric light in the evenings. Ultimately I believe it is stories like these that are the reason why this research lends itself so well to the various interpretative resources we have produced over the past year.

The new trails will be in use at Lotherton Hall and Standen from July, and are also available to download here.